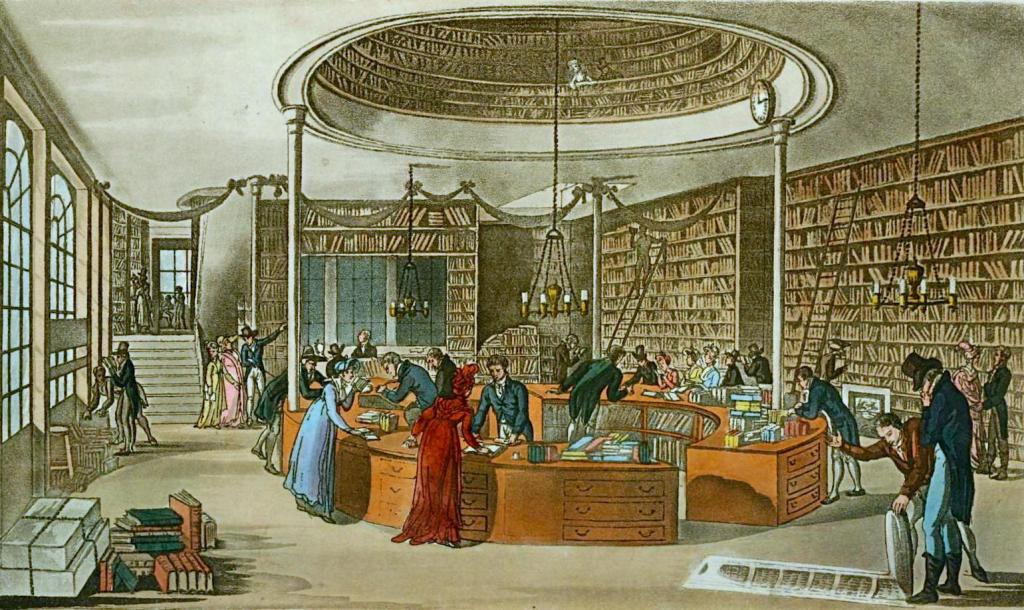

In 1794, James Lackington (1746-1815) revolutionized bookselling by opening one of the largest, most famous and successful bookstores in London called The Temple of Muses. In 1809, Ackermann published the following description of the mammoth enterprise:

“This magnificent structure is situated at the S.W. corner of Finsbury-square, and was fitted up for the reception of books in the year 1794. The dimensions of its front at 140 feet in length, and the depth 40 feet. The internal arrangement of the building is perfectly novel, containing on the base a ware-room, the capaciousness of which may be readily conceived from the circumstance of the Weymouth mail, with four horses, having actually been driven round it at the time of its first opening. This room, which is 15 feet in height, is supported by pillars of iron. On one side are distinct offices for counting-house business, wholesale country trade, and a department for binding, terminating with two spacious and cheerful apartments looking toward Finsbury-square, which are elegantly fitted up with glass cases, inclosing books in superb bindings, as well as others of ancient printing, but of great variety and value.–These lounging rooms, as they are termed, are intended merely for the accommodation of ladies and gentlemen, to whom the bustle of the ware-room may be an interruption. Solicitations have been strongly and frequently made to confine these rooms to the purposes of a subscription library, a plan which would no doubt be highly lucrative to the proprietors; but the disappointment it must necessarily occasion to a very large portion of the public, has determined them to continue the establishment precisely on that free plan on which it was first formed… It is computed that not less than a million of volumes are displayed to view in this immense building, and when it is observed with what facility the demands of each enquirer are satisfied, it is a matter of astonishment that so large a collection can be so simplified and regulated…The vast quantity of books circulated by means of this emporium and the dissemination of literature promoted thereby, may be judged from the circumstance of no less a quantity than six thousand copies of the Spectator, and the like number of the works of Shakespeare and of Sterne, forming in the whole 150,000 volumes, having been printed by this house in one uniform impression, and actually sold within the space of six years…

Ackermann’s Repository of Arts vol. 1 (1809)

Perhaps more remarkable than the vast scale of this bookshop is Lackington’s biography. In his youth, he sold pies in the street and later trained as a cobbler. He writes that “My manner of crying pies, and my activity in selling them , soon made me a favourite [sic] of all such as purchased halfpenny apple-pies and plum -puddings, so that in a few weeks an old pie-merchant shut up his shop.”[1] Lackington was uneducated and illiterate, but from a young age, he recognized the value of books. He and his friends spent all of their money on cheap editions of poetry, plays, and classical literature in translation, and taught themselves to read. His love of books is perhaps most exemplified by the fact that, instead of buying a Christmas dinner, he spent his last half-crown on a book of poems:

At the time we were purchasing househoļd goods, we kept ourselves very short of money, and on Christmas eve we had but half- a-crown left to buy a Christmas dinner. My wife desired that I would go to market and purchase this festival dinner, and off I set for that purpose; but in the way I saw an old book shop, and I could not resist the temptation of going in, intending only to expend sixpence or ninepence out of my half-crown. But I

“Anecdotes of Shoemakers” Chambers’s Miscellany of Instructive & Entertaining Tracts, vol. 16 (1871)

stumbled upon Young’s Night Thoughts, forgot my dinner, down went my half-crown, and I hastened home, vastly delighted with the acquisition. When my wife asked me where was our Christmas dinner, I told her it was in my pocket. ‘In your pocket ?’ said she; ‘that is a strange place! How could you think of stuffing a joint of meat into your pocket?’ I assured her that it would take no harm. But as I was in no haste to take it out, she began to be more particular, and inquired what I had got, on which I began to harangue on the superiority of intellectual pleasures over sensual gratifications, and observed that the brute creation enjoyed the latter in a much higher degree than man; and that a man who was not possessed of intellectual enjoyments was but a two-legged brute. I was proceeding in this strain— ‘And so,’ said she, instead of buying a dinner, I suppose you have, as you have done before, been buying books with the money?’, I confessed I had bought Young’s Night Thoughts. And I think,’ said I, “that I have acted wisely; for had I bought a dinner, we should have eaten it tomorrow, and the pleasure would have been soon over; but should we live fifty years longer, we shall have the Night Thoughts to feast upon.”

Lackington’s bookstore was located at No. 32 Finsbury Place South in the southeast corner of Finsbury Square. At the turn-of-the-century, it was THE place to purchase books in London, not only because of its vast collection, but because it offered the cheapest prices. After Lackington’s death, his son continued the business until the shop burned down in 1841.

[1] “Anecdotes of Shoemakers” Chambers’s Miscellany of Instructive & Entertaining Tracts, vol. 16 (1871)

Leave a comment